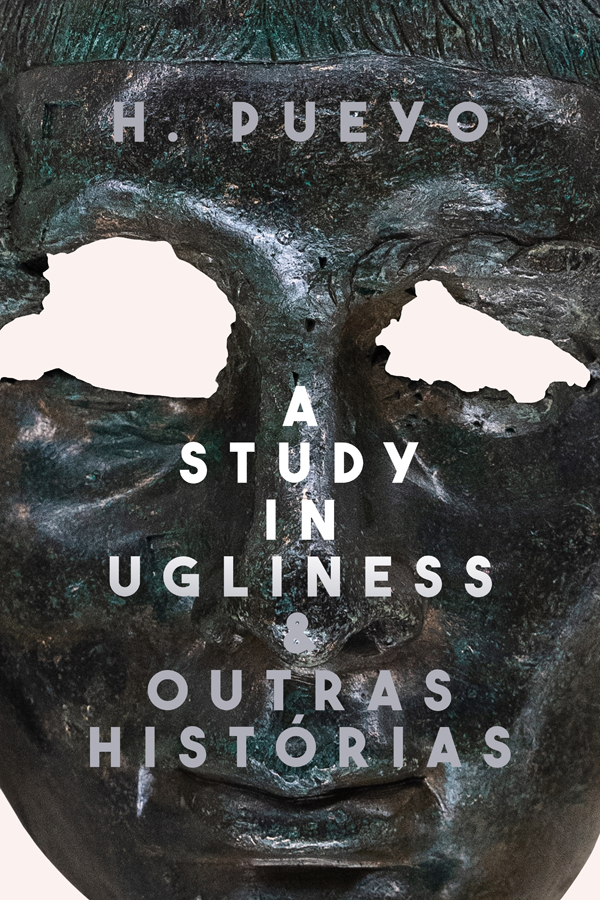

The title of H. Pueyo’s A Study in Ugliness & Outras Histórias cues the reader in immediately to its unique approach to translation by combining English and her native Brazilian Portuguese, “& Outras Histórias” being “& Other Stories.” The ten stories, translated by Pueyo herself, are presented with the Portuguese on the verso and English on the recto for each spread, a fascinating approach I haven’t seen before, which continually prevents the reader from forgetting or glossing over their linguistic dualism. The stories similarly prevent the reader from settling comfortably into the world we live in; using horrific sexual violence, cruelty, and ostracization to tell stories of the reverberating impacts of trauma. Some are more successful in this approach than others, but the most powerful stories here are able additions to the canon of weird fiction.

The English language falters sometimes, slight miscalculations in phrasing or idiom that I found jarring (“I couldn’t remember in the moment that I didn’t see them in a while,” or “so does him” or “it’s been a while he doesn’t eat,” that sort of thing). There are times it finds its way into an incredible phrase: “dry blood cluttered around a laceration” is perhaps the most remarkable, gore promulgated by means of a word usually reserved for stray papers and junk. It’s a nice encapsulation of the way that these stories combine the prosaic, day-to-day misery of patriarchy with more shocking moments of outré horror and the supernatural (which is not to deny the shocking moments of outré horror incumbent in patriarchal reality, of course). In the title story, Basília, an outcast, queer and aggressively uninterested in fitting in or adapting to her boarding school peers’ and teachers’ beauty standards, abruptly finds a new roommate sharing her room, and everyone else acts as if she’s always been there. Gilda is as physically beautiful and put together as Basília is not, but shares her aggressively disaffected outlook, and turns out to have emerged from a kind of rotten magic mirror, which the two girls proceed to use to torture their classmates. “I’m content in my ugliness, […] I fear most being trapped by their ideas of perfection. Let me rot any day.” Basília tells Gilda. “Ugliness, you say… That’s not how I see it. […] Sometimes, things are out of place. Sometimes places are inadequate for the things in them,” Gilda replies. They cut off their classmates’ pony tails and send them to the rotten world, and the mirror returns them as glistening pig intestines. They put a prized cat through the mirror, and it returns inside out and stinking. The mirror, not just reversing images but conceptual reality itself, literalizes the roommates’ gleeful inversion of the effort the teachers are urging Basília to put into her appearance, the perfect symbol for a story about perspective and outward appearances.

Where Basília rebels against the trauma of social expectations, two other stories take place in the traumatic aftermath of harrowing sexual assaults against school-aged girls. In “Mob, or the People vs Nadia Marijuán,” a popular boy sexually assaults the class outcast while their classmates watch. His guilt manifests as redness perpetually dripping off his hands and body, staining everything around him, while her trauma becomes viscous cords protruding from her ears, twisting into letters reading out insults and victim-blaming, mirroring the gossip of their classmates and Julián’s insistence that Nadia is to blame for attracting his attention. The story is structured as a trial, sectioned into The Injury, The Jury, The Parties, The Trial, The Verdict, bouncing between Nadia and Julián’s viewpoints, and is as much about the mob’s active participation as witnesses, the trauma inflicted by their jeering refusal to intervene, as it is about the boy’s physical assault. Sure enough, their culpability also has a fantastical physical effect, their itching eyes driving them to incredibly grotesque results. “I don’t want to turn out like them,” Nadia – ugly, unpopular, uninterested in fitting in – and Julián – attractive, rich, but now also ostracized for his crime – tell each other, even as he is dragged down into self-inflicted violence with the rest of their peers. It’s a heavy story tackling revictimization and society’s lack of compassion for survivors, but the narrative pulls in a few too many directions.

A more assured take on the same themes, “Rabbit’s Foot” picks up a similar story a decade after the fact, centering a woman who had been sexually assaulted by a group of friends while in middle school. Its first sentence is one of Pueyo’s best, alarming the reader immediately and setting the scene of precarious self-deception: “Everything was under control, except the alarm system shouting for attention, the noise piercing into her headache, except the cracked glass of the windshield.” The protagonist, reeling from a car accident, is seemingly rescued by a group of strangers (seemingly). Raíssa – or “Bunny,” for her rabbitish appearance and demeanor, her “always present instinct of running away” – suffers from prosopagnosia and anomic aphasia, and her haziness and desperation as people around her drift in and out of focus, her uncertainty about their identities and what’s happening to her now and what had happened to her before, is the high point of the entire collection. The strangers, inevitably, turn out to be her past assailants. Rather than karma, they blame Raíssa for their bad luck in the decade since – like the classmates in “Mob,” they deny their own agency and culpability. Raíssa, meanwhile, had refused to hold on to the details she knew about her victimizers and allowed her memory of the assault to drift into “peaceful oblivion” (which leads her, in a further echo of “Mob,” to blame herself for being vulnerable to revictimization) and the story is about her grappling with her trauma and regaining her sense of agency in the present. It’s an excellent, harrowing story.

These examinations of trauma and the weight of the past on the present, dealt with well in “Mob” and excellently in “Rabbit’s Foot,” also motivate the collection’s final, most transgressive, and longest entry, “Saligia,” which is less effective. It’s a werewolf story (in a nice metaphorical take on cycles of abuse and inherited trauma), but its motions toward the Gothic turn into pastiche, unevenly implementing a great structural idea: SALIGIA is an acronym for the seven deadly sins (in Latin Superbia, Avaritia, Luxuria, Invidia, Gula, Ira, Acedia), and the story’s seven sections center seven different members of a nineteenth century upper-class family, each of whom models one of the sins. The characters, though, never really move beyond archetype, and while the story’s overwrought melodrama suits the Gothic approach, it wears thin in such a particularly intense concentration of the rotting, overwhelming, sometimes exhausting cruelty suffusing this book – one might not be surprised that these Gothic sinners are rapists, child abusers, and murderers.

“Saligia” gestures toward social issues – the avarice incumbent in the family’s extreme wealth, racial disparities between the European family and the daughter of an Indian family whose marriage into the family kicks off the story – and the more Pueyo’s stories focus on the sociocultural context in which they take place, the stronger they are. She’s particularly incisive about patriarchal violence, clearly, but the context of Latin American (sometimes Brazil, sometimes Argentina) political history reverberates through her stories as well. “Juan Clemente’s Well,” narrated from the point of view of a colonial church, centers trauma in the form of a lachrymose statue, tainted by the degradations of military torturers. It’s a brief piece, essentially plotless, about – again – the dangers of turning a blind eye to trauma, about perpetrators looking for forgiveness (or not), about guilt and culpability. Military oligarchs also populate “An Open Coffin,” a story up there with “Rabbit’s Foot” in its narrative surety and sense of accomplishment, a brief tale of a woman hired to tend to an embalmed corpse preserved in the foyer of a great house. Recurrent visitors to the house reveal themselves to be reactionaries, demeaning and condescending to the woman, desperate for a return to their country’s past greatness under the general’s command. It reminds me, obliquely, of Cortazar’s classic “House Taken Over” (1946), the mysterious, displacing interlopers of the older story replaced here by pilgrims desperate to pay homage to a corpse – beautiful, perfectly preserved, but still lifeless and inert. Both stories share the feel of a political allegory without devolving into polemic.

Although A Study in Ugliness & Outras Histórias is a touch uneven as a collection, with several of the stories collected here faltering (some in interesting ways I’ve tried to lay out here, others by failing to thread the needle between a lightness of touch and heaviness of subject matter), her abject portrayal of patriarchy and sexual violence reaches for, and often succeeds, in using horror tropes in interesting, mature ways rather than for sophomoric transgression. “Rabbit’s Foot” and “An Open Coffin,” especially, deserve attention from everyone interested in horror written outside of the Anglosphere.

Zachary Gillan

Zachary Gillan is a critic residing in Durham, North Carolina. He blogs infrequently at doomsdayer.wordpress.com and tweets somewhat more frequently at @robop_style. His reviews have appeared in Strange Horizons and Ancillary Review of Books, where he’s also an editor.