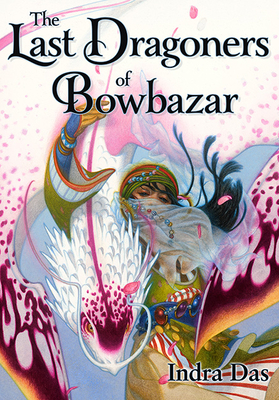

I read Indra Das’ The Last Dragoners of Bowbazar shortly after our non-fiction editor Karlo Yeager Rodríguez commissioned Shinjini Dey’s wonderfully insightful essay we ran in Issue #8. It was one of the best fantasy books I’d read in years so I was very excited about this interview. Indra spoke to me about everything from the cultural diversity of Calcutta and how he imagines it in The Last Dragoners; Hindu nationalism, resisting fascism in India, and solidarity with Palestine; his excitement about the future of Indian genre fiction; his love of film, and a boatload of other equally fascinating and important topics. I hope you enjoy this interview as much as I did, Indra was a delight to talk to.

***

One of the major themes of my reading of The Last Dragoners of Bowbazar is capturing and reclaiming a sense of the cultural diversity of Calcutta. What made you want to explore this as such a central theme, if I’m not totally wide of the mark?

I didn’t start out wanting to explore anything specific—this novella grew from an image in a dream, which I transcribed (it’s the very first scene in the book) and then followed to the rest of the story. But you’re not off the mark at all. I think that emerged organically as a central theme because Calcutta (or Kolkata) is my hometown, and its multiculturalism is one of the things I love about it—and one of the things about the city that’s slowly eroding because of the entropy of capitalism. Kolkata isn’t an easy place to find jobs, so many of the city’s multicultural enclaves—the Chinese, Jewish, Armenian, Anglo-Indian populations among them—are emptying out and fading because newer generations are leaving. And of course, there’s the situation in India itself, its broader multi-ethnic, multi-cultural, multi-religious nature under threat by the fascist regime under Prime Minister Modi and his party the BJP, a government ten years into its tenure (and getting five years more, albeit forced into a coalition after losing their supermajority this last election) and determined to destroy the country that was and replace it with a homogenized ethnonationalist Hindu Rashtra run by oligarchs.

The ever-thickening atmosphere of intolerance towards minorities in India (connected to and separate from its intolerance for the majority of Indians—the poor and oppressed castes, who far outnumber the upper caste elites) contributed to Dragoners becoming a story about migrants (refugees, in fact). I was writing the first draft during the pandemic’s early surges, when Hindu supremacists got busy blaming the spread of disease on ‘dirty’ Muslims, the Chinese, and ‘foreigners’ in general, as per the fascist textbook. Kolkata isn’t under the BJP as of now, and is known for its multiculturalism, but of course that doesn’t mean it’s in any way immune to the vicious bigotry that ensnares India. Attacks against Muslims weren’t rampant here as far as I could tell, but there was a rise in racism against the city’s Indo-Chinese population at the time, including boycotts of our numerous and treasured Chinese restaurants (whose cuisine is syncretic and unique and, might I say, divine).

The Covid-inflamed rancor was new, but the casual racism of Indian society isn’t, and includes India’s own Northeastern ethnic groups, including tribal populations. Hence the kinship my main character Ru (who is mistaken for a Northeasterner by his schoolmates) and his family find with their neighbors in Chinatown, a fellow immigrant population. And hence the focus on the two restaurants run by the Chens and Ru’s family. Food is an important part of cultural exchange, communication, connection. ‘Calcutta Chinese’ is a culinary institution, so why not write about how an extradimensional culture might acclimate their cuisine to this city and reality?

We ran a wonderful and very thoughtful essay on The Last Dragoners by Shinjini Dey a few issues back, and I just want to quote a short section and get your thoughts on it. ‘Das’s work has often been called magic realist for infusing his literary landscape with magic. I see it differently: the fantastic elements prop up the realist aspects, rather than the other way around. The magical elements do not explain the realism, like superstitions are said to explain common-sensical beliefs, but render the landscape with a shimmering unknowability that avoids all explanation.’ What does magical realism mean to you, and do you think The Last Dragoners falls under that banner? How do you approach the dichotomy of explanation versus ambiguity in your work?

I loved that essay—thank you for publishing it, and to Shinjini for writing it. I think she answers your question better than I can. I don’t like to be prescriptive about how readers describe or categorise my work. I love trying to rupture the cultural membranes between genres, have everything leak into everything else. Everything is fluid. We’re fluids, shitty sentient sacks of water and stargoo. Fiction is a fluid emanation. Gender is. Everything we are and create is fluid that hardens and calcifies into the sharp shapes of civilization. Our selves are fluid. And so on, you get the point, as I wander away from it. Art is fluid too, if we let it be. Genre is a necessary tool sometimes, for cultural discourse (neutral, not referring specifically to the cursed version that social media gave birth to), archival and recall, marketing. But I’ve always found that fandoms give genre too much prominence, strengthen the walls between things. Let things intermingle, confound, confuse. I do sometimes call my fantasy writing set on Earth ‘mythic realism’, mainly because I like how that sounds. What is that? Who knows, really. There’s the ‘enchanted’ realism of magical realism, where anything can happen and it’s just a part of that otherwise mundane reality (dream logic). My fantasy often follows the stylistic leanings of magical realism, but is closer to the narrative coherence and ‘world-building’ (to use a contested term) of fantasy, wherein the dreamlike aspects of a story come from the mythologies (the source, after all, of modern fantasy) of the world(s) being in some way real. But I love it when dream logic infects the hard lines of perceived reality, making it more fluid. Art lives there, whether realist or not, because it’s all imagined, it all comes from that dream space, our yearning to grasp all that we cannot understand about ourselves, all that we cannot perceive about the universe, our wonder and terror and sadness, and place it in a simulacrum of ‘reality’, as our brains do every night when we dream. So whether or not I explain things or leave things ambiguous, it comes down to me trying to replicate the feeling of a dream where something impossible is happening, but your brain tricks you into believing it is entirely real. That doesn’t necessarily require any explanation at all.

There was an exciting announcement recently that Westland Books has launched India’s first dedicated SFF imprint, called If. It surprised me to find out there were no Indian SFF imprints before now. What’s your perception of the current state of Indian genre fiction, and how do you think it will change in the future?

Samit Basu’s ‘Gameworld’ trilogy of fantasy novels (somewhat in the vein of Pratchett and Douglas Adams, though also influenced by Basu’s clear love of more epic fantasy, classic videogame RPGs, the Indian epics and myths, etc) broke out as a hit cultural phenomenon in the early 2000s, when they were marketed as India’s first English fantasy novels. But publishing kind of lost interest in the genre after that, with Indian SFF novels generally slipping out amid avalanches of other more popular genres, usually barely making an impression on Indian readerships. Indian anglophone SFF and horror readers have long preferred the foreign (mainly western) works that they (and I) grew up with, and have had trouble outgrowing that influence. I think younger generations of cross-genre/SFF readers in the country began to diversify their reading more in the twenty-first century (though I have no idea about the youngest generations’ reading habits, what with the many distractions of this dystopian and collapsing world), which has been aided a lot by the internet, online magazines (now in peril for various reasons), and slow gestures toward ‘diversity’ in western publishing (now rebounding as the white supremacist imperial core of capitalism grows frantic and rabid about its own unsustainability and slow collapse). A lot of Indians publishing anglophone SFF got into it because of the increased accessibility for submitting to Western SFF magazines. Including me.

But coming back to Indian publishing itself—most of our editors are versed in the book genres that are popular in India, which does not generally include desi SFF and cross-genre speculative fiction. With the exception of Indic ‘mythofiction’; epic fantasy novels based on Hindu mythology, a bestselling genre catered to Hindu nationalists (which I assume doesn’t require very much editing at all), and a distinct market in India (separate from fantasy novels based on Hindu myth written by diaspora and published abroad). This means most Indian publishers have no idea how to market SFF books effectively—especially weirder ones with cross-genre appeal. So SFF books written by resident Indian authors (not including diaspora here, because that’s a different context) tend to be drowned out by the competition in other genres. I mostly don’t even see Indian SFF novels shelved in Indian bookstores. They usually get to me via blurb copies or online retailers. Because of this, some Indian SFF writers end up publishing primarily abroad, and those works don’t really get reviewed or noticed by the mainstream literary scene here.

Since India has very few dedicated SFF magazines (included in this small number are the Indian-Pakistani Tassavur magazine and Mithila Review, which I believe is on hiatus), no dedicated spec fic awards, and little localized and well-informed, cogent cultural criticism focusing on homegrown speculative fiction, anglophone ‘Indian SFF’ as a whole has never really taken off. There are good Indian SFF critics—but they’re generally writing in foreign publications (or in newsletters, blogs, or in the academic sphere).

India hasn’t had a non-diasporic breakout global SFF hit, either culturally or economically, on the scale of, say, Cixin Liu’s books. I think that’s because we don’t culturally nurture this spectrum of genres, despite being a petri dish of various mythologies. But what there is is fascinating for its stylistic and thematic diversity. Indian SFF and cross-genre writers tend to be doing quite varied work that can’t be lumped into one literary movement. And there are some breakouts on a smaller scale, like Lavanya Lakshminarayan’s dystopian tech satire mosaic novel Analog/Virtual being published in India and then going on to become well received as The Ten Percent Thief in the west (it got nominated for the Arthur C. Clarke Award). My own debut The Devourers was first published in India by Penguin India, but going by the numbers (which are always foggy in this country), it did not and does not sell well in my home country. I still haven’t earned out that edition’s advance. It’s certainly no bestseller abroad, but the difference in sales is stark, and it has legs outside India (imagining the book as a creature now).

Which is all to say, I welcome Westland’s If label, and hope it’s a sign that India (and South Asia) is getting closer to embracing and reading its own spec fic authors. Their first book, Gigi Ganguly’s collection Biopeculiar is a delightfully strange and often distinctly Bengali book, often focusing on giving voice to the natural world beyond humanity, as well as painting a variety of genres with a bright streak of fabulism.

Any discussion of Indian publishing and mainstream literature should also note that it is unsurprisingly dominated by upper caste Hindus and the upper middle class, among writers and editors and publishing staff. For Indian publishing, SFF/H and otherwise, to enter a new era where it can flourish and emerge from stagnation, we need to have more minorities and oppressed castes working in publishing and getting their work published.

We’re doing this interview shortly after the death of Bernard Hill, perhaps recognisable to most people for his role as King Théoden in The Lord of the Rings films. I follow you on social media and saw you paying tribute to him for his role in Peter Greenaway’s Drowning by Numbers. As an appreciator of both Hill and Greenaway I’m curious what it is about this film that captured your attention, and what struck you as notable about Hill’s performance in particular?

I mentioned Drowning by Numbers out of all his work because I’d seen a link to a rip of the movie on Twitter being shared in Hill’s honour, and wanted to share the same on Bluesky, because it’s an incredible film. I feel like Greenaway’s films are in that fantastical dream space that I was talking about earlier—their worlds aren’t ‘realistic’, but they breathe with a life of their own that animates them into their own form of reality, instead of a pale imitation (like, say, the ‘reality’ of latter day Marvel Cinematic Universe). They are folklore, modern myth, universes of their own. For people who know Hill as Theoden King, it’ll be a treat to see his more puckish side in Drowning by Numbers, where he plays a mortician in thrall to a trinity of murderous women who more than resemble the Fates. Also, can I just say that as a teenager I cried when Hill, all tragic dignity and shocked acceptance, stands aslant on his sinking ship and goes down with it as Captain Edward Smith in Cameron’s Titanic, which I went to see with a gaggle of classmates in ‘97. We all gasped and laughed and wept together at the utter spectacle of that movie, it was glorious. I just realized as I’m recalling this that I wove this memory into Ru’s life in The Last Dragoners of Bowbazar. My brain knows me.

I’ve actually seen you make some insightful comments about a number of somewhat niche, lesser known, some might say sicko films. Do you consider yourself something of a film buff? What are some hidden gems you wish more people had seen?

If I’d lived a different life, I’d have tried to make movies. I’m a sensory, visual storyteller. I was drawing as a kid long before I was writing stories. When I lived in Vancouver, I was an unpaid critic for a startup entertainment news site that folded later. Even with not a loonie in my palm for the work, I loved going to those early morning screenings and watching a movie for free (for my free labour, rather), bleary-eyed and clutching a cup of the acrid coffee set up outside the theatre, the grumpy banter of the old guard critics around me, wandering out into the afternoon to my favourite café (Our Town, probably gone by now) and writing out my thoughts. Of course, ‘movie critic’ is not a job most people can have or keep nowadays (it wasn’t back then either), so there goes that dream.

But I can still ‘review’ movies on social media, so I do. Sharing art with others is one of life’s greatest joys. Movies (and music) are great for that, because you can actually experience them simultaneously with others quite easily, unlike books. Social media film chatter (when it’s not embroiled in the usual socmed discourse nonsense) isn’t quite the same, but it’s a related feeling of communal sharing. I can’t claim to be an expert on niche and, yes, sicko films, but social media has been a treasure trove for finding recommendations, so I try and pass on the favour whenever I can. Even more so because so much modern SFF movie/TV discourse on socmed is dominated by big IP.

Anyway, lesser known gems—for true sickos, the Evil Dead Trap duology, both standalone, Japanese horror, exceptionally nasty, nothing to do with Evil Dead. The second one (Hideki) in particular is a masterpiece, written and directed by Akira co-writer Izo Hashimoto, an absolutely gorgeously shot vision of urban isolation that portrays modernity like a neon-veined membrane over the old god of patriarchy (which ensnares all genders—the film’s about a serial killer who’s a woman). The live-action Hong Kong cinema adaptation of the Japanese manga/anime Wicked City, a work of urban dark (but absurd and funny) fantasy action so brilliantly creative in its low-budget practical filmmaking, and so deliriously batshit, that it’ll make you feel like you’re on drugs or want to be on them. Lizzie Borden’s classic lo-fi socialist-futurist Born in Flames, one of the most convincing portrayals of fictional revolution and post-revolution I’ve seen. Borden’s Working Girls is another must-watch, a beautifully lived-in, funny, subversive workplace drama about sex work. Sally Potter’s ravishingly Romantic Woolf adaptation Orlando, not sure if that counts as ‘lesser known’, but it should be considered an iconic modern-mythic exploration of gender fluidity, much like the novel. Recently really enjoyed two experimental low-budget, lo-fi cyberpunk films, German 80s counter-cultural curio Decoder, and Abel Ferrara’s 90s William Gibson adaptation New Rose Hotel.

Among more recent lesser knowns, I’ve loved Bertrand Mandico’s trippy as fuck, genre and gender-fluid, practical-made sci-fi/fantasy epics After Blue and She is Conann. You Won’t Be Alone, a visceral yet meditative historical drama about shapeshifting witches in nineteenth century Macedonia, is among the most underseen folk horror/dark fantasy gems of this era. I felt like it had such an immense kinship with The Devourers, like the filmmakers were channeling exactly what I was feeling writing that book.

This isn’t a question at all related to writing, film, or art in any way, but I think Seize The Press is a magazine that wears its left wing, anti-imperialist values proudly on its sleeve, and you are a vocal critic both of Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist government in India and Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza. What compels you to speak out against injustice at home in India and abroad in Palestine?

My hope is that the activists, journalists (the real ones), lawyers (the good ones), refugees, protesters, survivors, resistance fighters, the oppressed will find some measure of strength from the collective voice of those who are on their side. That the more progressive supporters of the evils of our nation states—and there are many—will be shamed for their moral cowardice. The fact remains that all of us in the ‘elite’ sphere of the world, who can afford access to ample tech, shelter, food, water, are complicit in a historical event like Israel’s genocide in Gaza (I’m published in India and the USA, both nations that are sending bombs to massacre Palestinians, the latter in far greater proportion of course as Israel’s greatest global patron). Or the genocide in the Congo, where the minerals for our phones and other devices are extracted by workers, often children, in horrific conditions amid perpetual violence fomented by proxy wars. We should be talking about how we’re complicit, so that we can begin to do the hard work of dealing with that, of divesting our institutions from machineries of mass dehumanization for the benefit of capital (and that is what nation states are, fortresses of capital). Until it is acceptable for everyone to admit our complicity in evil, little can be done—and sadly, that involves talking about it repeatedly.

I cling to those videos of Palestinian children in refugee camps telling the world that they are proud of the American students protesting their government’s complicity in the Gaza genocide in colleges, or thanking Macklemore for the song about little Hind Rajab surrounded and murdered by the IDF in a car among her dead family. I hope that my sharing their fundraisers or bearing witness makes some difference to their lives. If I didn’t say anything at all, the horror would eat me up inside, and I myself would lose any semblance of hope, so it’s also a selfish cathartic impulse. The point is to normalize anger at the state of my country, of the world. This isn’t, shouldn’t, be normal. The ravages of colonialism, imperialism, capitalism, fascism, all working in unison, will destroy our world unless people fight back. The least I can do is support the ones who really are fighting, let them know they’re not alone in their anger. Talking about things is the beginning—there has been a sea change in how people think of Israel’s genocidal aggression among younger generations, and social media has played a part in that. That makes no difference to the carnage on the ground unless governments listen to their people, which they don’t, obviously. But as happened with South Africa’s apartheid regime, one hopes that this widening recognition of a state’s obvious rogue actions leads to a cumulative pressure on our governments to abandon their support of said state. There are other ongoing genocides of varying scale, like in Sudan, which barely get talked about at all, and hopefully that changes too. Some genocides are comfortably denied by western leftists too, because they were or are committed by regimes that are enemies of the US empire. This can be rather frustrating for those of us stuck with plenty evil regimes to contend with in the global south.

In a country like India, where even a Booker-winning writer and journalist like Arundhati Roy can be charged with ‘sedition’ by the government (and she’s just one among numerous less famous people targeted by the state, including Kashmiri scholar Dr. Sheikh Showkat Hussein, who was named in this case as well), ‘speaking up’ in spaces online and off is also just a way of staking your claim to your own country and space, even as it’s dominated by those who’ve accepted fascism and hate as their way of life. It’s a way of saying: fuck off, you will never not be losers, even when you win. There are many Indians who don’t even have that privilege, who cannot speak for fear of immediate repercussions, or censorship.

One of my favourite things to do in interviews is to find out what folks have been reading and if they have any good book recommendations, so to close things out on a more cheerful note, who do you think are some of the most exciting new voices in genre fiction and what have you been reading recently?

I’m going to do the South Asian solidarity thing and recommend some fellow authors from this region; Tashan Mehta’s wonderfully strange The Mad Sisters of Esi (published in India, hopefully editors abroad take note and broaden its reach), which is like a galaxy-spanning Piranesi (to be reductive); Samit Basu’s The Jinn-Bot of Shantiport, which was marketed as a sci-fi Aladdin but is far more than that, and a genuinely smart, funny, and rousing entertainment about the difficulties of revolution in a beautifully fleshed-out spaceport city that holds in itself a myriad satirical connections to contemporary India; Prashanth Srivatsa’s The Spice Gate maps caste and the politics of the spice trade onto a sweeping secondary world fantasy epic to fascinating effect. I just started Amal Singh’s The Garden of Delights, which I’m enjoying very much; I do love good cities in a fantasy stories, and this one has multiple beautifully imagined ones that clearly hearken to Miyazaki-esque dream-baroque. Then there’s Vajra Chandrasekera’s thematic duology of The Saint of Bright Doors and Rakesfall, both books which blow open the doors of genre and perception like flimsy cardboard. Chandrasekera’s like South Asia’s Delany, though their work is very different. I think he might become a genuine South Asian SFF phenomenon abroad, and deservedly so.

Moving beyond South Asia, Tlotlo Tsamaase’s Womb City is a ferociously strange Africanfuturist work that, again, shreds genre walls with aplomb while maintaining a pervasive sense of horror and Philip K. Dickian paranoia. A book that sometimes stumbles out of its nightmare fugue because of overly expository impulses, but when it’s great it’s skin-crawlingly so, and I’ve never read anything quite like it. This one needs no championing (though it was startlingly ignored by major awards)—but I found Gretchen Felker-Martin’s Manhunt to be a gut punch, thrillingly real and vulnerable and honest in its habitation of genre—really looking forward to her latest, Cuckoo. Jared Pechaček’s The West Passage is a magnificently weird (and gorgeously illustrated by the author-artist) fantasy epic that deserves to become a classic. I’ve shouted about Mariana Enriquez’s Our Share of Night many times, but am compelled to again. A monolith of a novel, absorbing the malign energies of the world and transforming them into something magical and alive. Reminded me of the effect King’s It had on me as a youngster. I’m also loving Tanya Tagaq’s Split Tooth, an autofictional work that’s so open it’s like a dream sprung from a wound—poetry, prose, horror, realism, all bound in the oneiric world of dream and memory. I still haven’t picked up Marlon James’ Moon Witch Spider King yet, but it’s on my shelf, and I loved Black Leopard Red Wolf, which had a perplexingly muted reception from the SFF world. Ooh, and in comics, don’t miss Deena Mohamed’s Shubeik Lubeik, Emil Ferris’ My Favorite Thing is Monsters (the long-awaited volume 2 just came out, and I must have it), and Deniz Camp’s 20th Century Men (art and lettering by Stipan Morian and Aditya Bidikar), all brilliant. I’m also excited for recent and upcoming books by many authors, including Sofia Samatar, Rivers Solomon, Kerstin Hall, Suzan Palumbo, Sarah Brooks, Paul Tremblay, Alison Rumfitt.

Finally, there was quite some time between releasing The Devourers and The Last Dragoners; do you have plans for any more novels or novellas in the works? What else are you working on now or do you have coming out soon?

Many plans for more novels and novellas, though nothing at the ‘talk about it’ stage. The Spanish translation of The Last Dragoners of Bowbazar by Rebeca Cardeñoso will be published by Duermevela Ediciones later this year. The first anthology I’ve edited, the latest volume in the MIT Press science fiction series Twelve Tomorrows, titled Deep Dream: Science Fiction Exploring the Future of Art, will be out October 8 this year, and can be pre-ordered here. I’m very proud of the work everyone featured in the book has done, so I hope that people will give it a try. The idea for the theme came out of my horror at seeing the directions monopolistic corporate control, the abomination of generative AI, and tech in general, is taking art, and seeing what a group of excellent and stylistically varied writers make of the opportunity to imagine art and artists in futures near and far, whether pessimistic or optimistic. Here’s hoping Deep Dream isn’t the last anthology I edit, because I really enjoyed putting it together.

Thanks so much Indra, it’s been such a pleasure to have you here.

Thank you so much for having me, it’s been wonderful. My gratitude for letting me ramble so uncontrollably. And most of all, thank you for the vital and valuable work you and your team do on Seize The Press.

Indrapramit Das

Indrapramit Das (aka Indra Das) is a writer and editor from Kolkata. He is a Lambda Literary Award winner for his debut novel The Devourers (Penguin Random House), and a Shirley Jackson Award winner for his short fiction, which has appeared in publications including Tor.com, Clarkesworld, and Asimov’s Science Fiction, and has been widely anthologized. His latest book is the Locus and British Fantasy Award nominated and Subjective Chaos Kind of Award winning novella The Last Dragoners of Bowbazar (Subterranean Press). He currently resides in his hometown.