When I read Gideon the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir, I knew who the murderer was before I knew it was a murder mystery. That’s because she was the only member of the core cast to be visibly disabled.

Disabled characters tend to be slotted into one of three archetypes: Victim (sacrificed to the plot); Villain (gives the hero someone to oppose); or Inspiration (motivates the hero by “overcoming” their circumstances). Therefore, the moment an obviously disabled character is introduced, readers can use context clues to predict which plot function they’ll be filling. In the case of Gideon the Ninth, not only was the culprit introduced in a way that emphasized her physical limitations, she was also the first person to be kind to the protagonist. Between her continued survival and character development, the text makes clear she’s an important character and for me it became increasingly obvious she’d be revealed to be a Villain as a knife twist.

As for why disabled characters frequently get stuck with the Villain archetype, it’s for two polar opposite reasons: as a signifier of their inherent evil, or as a signifier of their moral purity. The most general reason for the former is that many people prefer to think of disability as a punishment for wrongdoing rather than as something that can happen to anyone; according to this logic, disabled people must have done something to “deserve” their condition. That, combined with human biases against those deemed “other,” explains why people with scars and facial differences are overwhelmingly typecast as villains (see every James Bond film ever). Invisible disabilities are not exempt, either; mental illness, for instance, tends to be used as a synonym for evil. For example, slashers like Norman Bates are often depicted as being driven by psychosis, even though people with mental illness are no more likely to be violent than anyone else, yet are disproportionately likely to be on the receiving end of violence.

On the other end of the bigotry spectrum is the portrayal of disabled people as overflowing with the innocence and wisdom of childhood, suffering the greatest of indignities without a complaint. This is just as dehumanizing and infantilizing as the assumption that disabled people are helpless, sometimes to the point of being unable to lead fulfilling lives. When this assumption is presented unquestioned, the result is the Victim. This character utterly lacks agency, existing only for the hero to either rescue them or mourn their tragic fate at the hands of a particularly dastardly villain. But a character who couldn’t possibly do anything for themselves makes for an awfully convenient alibi. Enter the Hidden Disabled Villain. This character plays up their perceived helplessness in order to achieve their nefarious ends, leaving both the hero and audience gobsmacked that someone so weak and feeble could possibly undertake such crimes! Or at least, that’s how it’s supposed to play out. The “subversive” twist tends to fall flat because a hidden Villain is still a Villain, playing that archetype dead straight.

A good example of this sort of Hidden Disabled Villain can be found in Detective Pikachu. Howard Clifford is introduced as a benevolent corporate executive whose passion in life is peaceful coexistence between humanity and Pokémon. And if “corporate executive” wasn’t enough of a red flag, he also uses a wheelchair. His portrayal early in the movie leans heavily on the Inspiration archetype, which we’ll get to in a second, but it’s not long before he’s presented as a Victim. When the protagonist confronts him about his company’s unsavory activities, Howard gives an anguished speech about how he’s helpless, gesturing at his wheelchair like that explains why he can’t do anything about the “perpetrators” who literally work for him. Cut ahead, and Howard is revealed to be the actual mastermind, to the shock of absolutely everyone except the audience. And as an added bonus, his motivation is partly to get himself a “better” body, fulfilling the quota for “disabled person so desperate for a cure that they’re willing to throw away their literal and metaphorical humanity for it.”

The other attempted subversion of the Victim archetype is the Inspiration. Disability advocate Stella Young coined the term inspiration porn to describe narratives where disabled people “overcome” their disability in order to teach abled people how to be better versions of themselves. In mundane contexts, this usually means glurge-fests over disabled characters literally just living their lives, whether that’s going to work or getting invited to Prom. The next step up is the “What’s Your Excuse?” style inspiration, where a disabled person does something objectively inspiring, only for it to be framed as proof that if someone like them can do it, surely any abled person could do better! In SFF and horror, this can be exaggerated into literal superpowers, such as a blind person gaining enhanced hearing or the gift of prophecy to “make up for” their lack of sight. But even in these narratives, a disabled person’s amazing skills aren’t really about their accomplishments; they’re intended to serve as motivation for abled audiences.

In fiction, the three archetypes make for lazy storytelling. The bigger problem is that people have a nasty habit of applying these archetypes to real life. “Victim” is often synonymized with “burden,” which in turn is used as justification for all sorts of eugenicist policies. Inspirations, meanwhile, are model minorities held up as an example of what disabled people “should” be, implicitly positioning anyone who doesn’t meet those standards as deserving of exclusion and mistreatment. As a result, accommodations are denied because they’d be wasted on Victims who’d obviously be miserable no matter what. Yet in the very same breath, the people denying vital resources expect these Inspirations to weather their reduced quality of life without the slightest inconvenient complaint that would shatter the illusion that accommodations are unnecessary. Disabled people who dare to be anything but insipidly grateful for insufficient scraps of charity get labeled as “difficult” Villains. The prominence of the three fictional archetypes bolsters narratives driving injustice at the systemic level, and these narratives feed back into fictional portrayals of disability.

Because the use of the three archetypes is a systemic problem, an individual character who fits the archetype isn’t necessarily a bad character. This tends to be most true of Villains, since they have the most agency and therefore characterization of the three. The culprit of Gideon the Ninth has plenty of fans due to the way her character is fleshed out, and the same could be said of Jinx of Arcane. But even if every single Victim, Villain, and Inspiration were depicted in unproblematic ways, at the end of the day, all three archetypes exist for the sake of other characters. Maybe they motivate the hero to take on the villain, or maybe they are the villain the hero needs to stop. Either way, the numerical dominance of these three archetypes reinforces the paradigm where disabled people don’t get to be the heroes of their own story.

So what’s the solution?

The first and most obvious is to let disabled people tell their own stories. As disability advocates often say, “Nothing about us without us.” Efforts to increase diversity have met with some success, but more work is needed. Disabled people are still underrepresented in publishing, and less than one percent of TV screenwriters report disabilities. Therefore, disabled creators still have to deal with mostly abled gatekeepers who gravitate toward more familiar narratives where disabled characters can be neatly slotted into the roles of Victim, Villain, or Inspiration. In other words, the lack of authentic representation tends to be self-perpetuating.

When disabled people do muscle past the gatekeepers, they often shatter the three archetype system without even trying. Take the TV adaptation of Raising Dion. Actress Sammi Haney uses a wheelchair due to brittle bone disease, and so does her character, Esperanza Jimenez. Esperanza’s definitely not a Villain; though Dion initially finds her annoying, she’s on his side whether he wants her to be or not. She’s not a Victim, either. While the show doesn’t sugarcoat the realities of her disability or of living in a society where inaccessibility is the norm, it also doesn’t portray her as needing to be fixed. In fact, when a well-meaning Dion tries to use his powers to help her “walk,” she’s furious that he took her out of her chair without consent. Esperanza isn’t an Inspiration, either. She has plenty of smarts and social savvy, neither of which are “despite” anything, nor are her contributions treated as any more or less special than those of the other characters. In other words, Esperanza is portrayed as a normal girl who happens to be friends with a boy with superpowers.

The push for authentic representation, while well-intentioned, can have its own problems. First and foremost is the pressure to self-identify; not everyone wants to disclose their disabilities, and they shouldn’t be forced to do so in order to get published. This is doubly true considering that disabled storytellers are often pressured to educate abled fans with their stories, thereby being held to higher standards than abled authors. Second, the existence of both internalized ableism and lateral ableism (i.e., ableism against people with different kinds of disabilities): disabled authors are perfectly capable of perpetuating harmful narratives around disability. So while letting creators with disabilities tell their own stories is critical, there needs to be broader community participation in moving beyond the three archetypes.

When it comes to depicting characters with disabilities you don’t share, knowledge is power. Research the experiences of people who live that disability rather than relying on preconceived notions and the accounts of families and caregivers. It’s also a good idea to have disabled people consult on the project in question. For instance, when the creators of The Mandalorian decided to develop Tusken sign language, they brought in Deaf actor Troy Kotsur. More generally, there are plenty of disabled sensitivity readers who assess books and scripts for harmful stereotypes. These can all help authors spot their own biases, allowing them to develop nuanced characters that transcend disability archetypes rather than conforming to them.

In the previous paragraph, I said “disabled characters,” as in plural, for a reason. If a piece of fiction only features one disabled character, they often end up becoming a token, cosmetically increasing diversity despite functioning as a living stereotype. This isn’t necessarily the case; as the blog Writing With Color points out, sufficiently fleshed-out characters aren’t tokens. But if there’s more than one member of a group, it becomes easier to demonstrate the diversity within that group. One example is the Percy Jackson series. The idea that the protagonist’s dyslexia is a result of being a demigod would have positioned him uncomfortably close to the Inspiration archetype if it weren’t for the contrast with the downright bookish Annabeth. And Annabeth without Percy could have come across as “overcoming” her dyslexia rather than working with her brain to pursue her love of learning. By acting as foils for each other, both characters get to show off their complexity without their arcs beiing flattened down into overly simplified disability narratives.

Having multiple disabled characters isn’t a cure-all, however, and in some cases can make things worse. Take Arcane for instance. While the show’s gray-and-gray morality makes it difficult to classify the characters into heroes and villains, the level of visible disability certainly correlates to antagonism. Prosthetic limbs are used as shorthand for a tough opponent, while facial scars are most prominent on the characters most willing to get their hands dirty. At first glance Jinx and Viktor are two major exceptions. The thing is, Jinx is disabled by dint of mental illness, and while the show is refreshingly careful to clarify she’s not evil because of her psychotic symptoms, she’s still a literal terrorist. Viktor, meanwhile, is doomed to become the Machine Herald, and his increasingly desperate efforts to cure his terminal illness (which is visually equated with his mobility aids) is a classic supervillain origin story. So rather than introducing balance to the story, the abundance of disabled characters drives home the association between evil and disability – much like the overabundance of Villains in fiction.

Victims, Villains, and Inspirations are the dominant portrayals of disabled characters in fiction, but they don’t have to be. By opening the door to authentic rep, and through the mindful creation of fully fleshed-out characters, we can expand the narrative possibilities around disability. Following this advice can not only make the “who” in a whodunit less obvious, but can help make our communities more inclusive to disabled people.

Julia LaFond

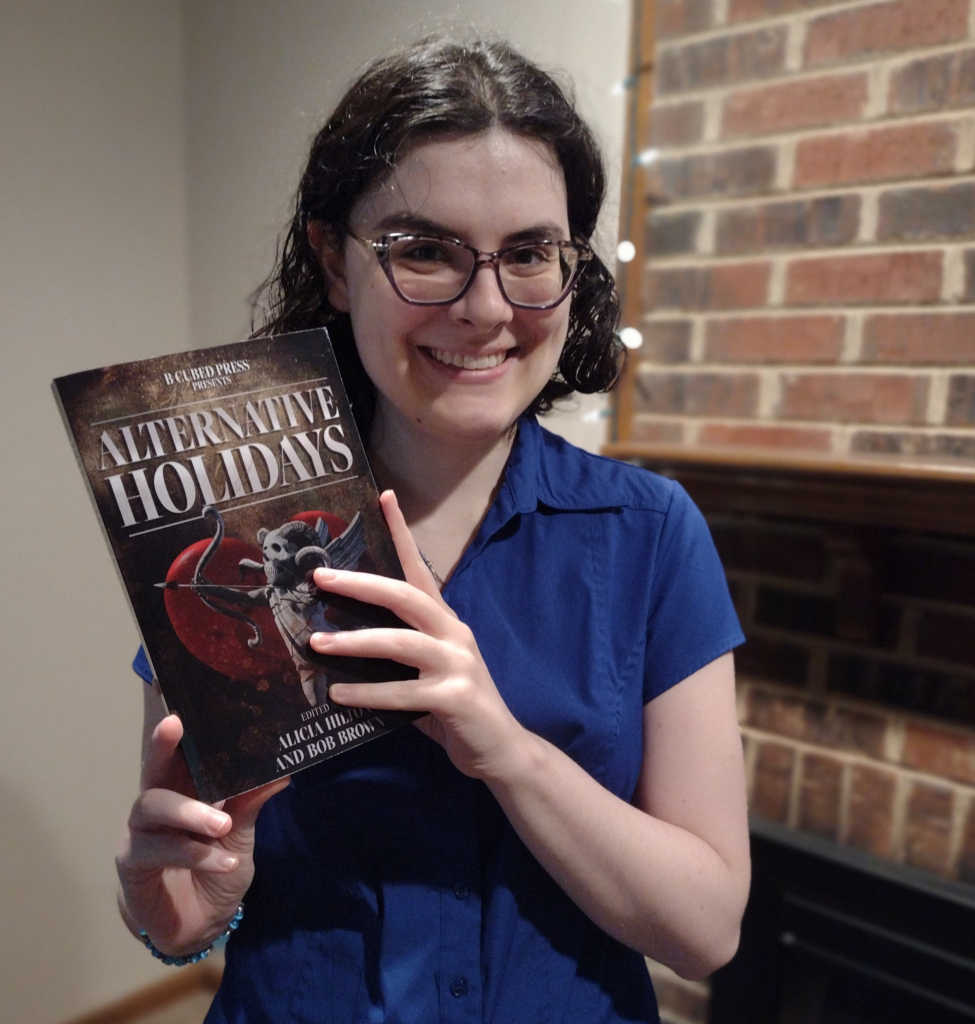

Julia LaFond graduated from Penn State University with a master’s in geoscience. Now she’s a writer; for fiction, she specializes in sci-fi, fantasy, and horror, with short stories featured in venues such as The Librarian Reshelved and The Martian Magazine of Science Fiction Drabbles. She also writes nonfiction on related topics, with her most recent piece featured in The Deadlands. Aside from that she strives to advocate for disability justice, working with her communities to improve access and dismantle unjust systems whenever possible. In her spare time, she enjoys reading and gaming.